Deconstructing a myth

or, an analysis

During the second year of my postgraduate I won a mildly prestigious travel grant, offering a sort of gap year of additional study.

That was how I began a post last November.

That opening line—although plausible—was a lie.

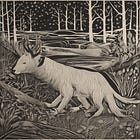

In fact, the whole post was a lie. It became the first chapter of a piece entitled The Sernox. Like always, I had no idea what I was doing. I just wrote, typing out sentences that sounded believable but with zero plan. All I knew was that I wanted to write about a myth. Something dark, dangerous, intangible—something steeped in folklore and set in Scandinavia Finland1, written as though it had happened to me. I didn’t know what I was beginning. I didn’t know how that initial notion of an idea would change. I didn’t know how it would consume me.

The Sernox is finished now. It’s short, just seven parts long. I’d like to pretend that seven holds some significance, that there was a reason for that number. I even went so far as to craft a fake sentence about it. I deleted that. There are enough lies here already.

The point is, I managed to write the story to completion. It hit draft one. Or is it draft zero? I don’t know. I’m not a writer. Anyway, I actually finished something. Like, actually finished it. And I love the story, flawed and brutal as it is. Maybe I love it enough to open up to some of those close to me—those who have no idea I even write—and say to them: “Would you read this messed up thing I wrote?”

(I don’t know where else to put this so I’m going to put this here: thank you to all who read, liked, commented, and shared The Sernox2 as it was being written. Your passion for the unfolding of the story—especially the fourth part, which seemingly contained just the right somethingness to become the apex of my little publication—will forever mean everything to me.)

I’ve been reflecting on this and the journey of the last year. Things I’ve written. Things I’ve read. Some introspection on the way I’ve gone about things3. Most of the time I don’t ask a story what it is or where it’s going, instead giving in to acceptance as my fingers coalesce with the keys. Only later do I look back on parts and think oh, so that’s why that bit is there. There’s rarely a solid plan, is what I mean. It’s a stupid way to go about things. I don’t know about structure, form, arcs or acts, about prose or grammar or a subordinate clause. Because I’ve had no training.

I just know what I like.

Of late, I have begun to scratch at the surface of books with a pencil until I can see the rules of wordplay etched beneath the ink.

I’m delaying myself. I want to scratch at the words underneath The Sernox. If you’ll indulge me.

She smiled. And I died. Right there on the platform, my body collapsing limp and flowing over the edge, to pool across the tracks and await severance from this world.

After the opening chapter, I realised the whole focus was going to be on Emmi. It had to be. It needed to overtake and dominate, mirroring the infatuation of the protagonist. It couldn’t be a simple brooding love. There needed to be something more, a distillation of feelings, raw and tangible; this needed to have an equivalence with nature, the stark isolation of a forest, the beauty of each star, the vibrations in every atom of a body, the cruel intoxication of another.

I wanted the details of the surrounds to be minimal but at the same time intricate, with a current of melancholy and a framing of longing flowing throughout. I wanted Emmi to be ethereal, to be surreal, for her way of speaking to border on the uncanny. I wanted all this to be the distorted recollections of an unreliable narrator. That had to come from the prose, I realised (it’s why there’s a tonal and stylistic shift after part 14). That might be too florid for some. I understand if you don’t like it. But I had no choice. It was the path I had to follow. I have a fascination with how combinations of certain words feel, stemming from my love of Haruki Murakami and, more recently, the staggering prose of Mircea Cărtărescu. I strove to build a style that was as rich and poetic and languorous as I could manage. One that was filled with words that maybe I didn’t even know were real. I agonised for hours over single sentences. Nothing has ever taxed me more than writing some of the paragraphs of The Sernox.

As the cocoon of my youth unfurled, I came to witness these shifts. Days shortened, nights encroached. The seasons exhaled their relief as winds couriered news of the next. The world moved, and I noticed where once I had not. I felt where once I was numb.

All because of Emmi.

So here’s another thing—OK, three things—I have come to accept: I adore the first person; I am uncontrollably drawn to writing about relationships; I am fascinated by the notion of an unreliable narrator. All three are intertwined, of course. First person is, to me, the most beautiful and compelling form of literature. It is a constrained and personal account. It is the closest we come to our own lives, ones that suffer their own unreliable narrators, existing and shaping our stories each day, the stories of catastrophic love and despair. It fascinates me.

I wanted the reader to be transported into all the moments the protagonist recounted, to be yanked periodically back to his present where he laments a jealousy and, eventually, a horror that torments his soul. The expectation of the reader, I hoped, was that The Sernox was real, that Emmi’s myth bordered with reality and that the story would veer into the supernatural. That would not be so. The creature was Emmi’s infatuation; Emmi was the narrator’s. There was, in the end, only one way I could make her monster be real.

As months crumbled and daylight fled, the terrors—swollen and bleak and always with the scent of blood—whispered their uncaring hurt, forcing me to the forest at dawn, to seek a clearing where I could sear the dread from my eyes.

I don’t know if I’ve given any substantial sense of anything here. I don’t know if I’ve come any closer to explaining what this story is.

Perhaps that is the way it should remain: As intangible as Emmi.

Now, if you’ll forgive me, I’m going to take a walk around a lake.

Thank you, Jamie. The print edition will be corrected, except for your signed copy that will have Scandinavia still written in it. Just for you.

I wanted to refrain from linking out in a post, but I realise it may frustrate if there’s not an easy way to locate the beginning, so here:

Special thanks to the brilliant

, whose “retros” pieces served as an inspiration here, along with the sublime , whose Reflections on his own (equally sublime) poetry are magical. Both authors are well worth your time.Meaning, most likely, that the initial chapter will need to be tweaked.

"I’m not a writer." you say? That is a lie. We know the truth. Everyone does. You are a writer, passionate and gifted. Nobody is perfect and knowing all the rules doesn't make you a writer. Writing does. Here's to a finished story and to many more to come, ahem, Brae... ;)

People have this weird thing about what makes you an artist or an author. If you walk most days, you consider yourself a walker, if you read you’re a reader, likewise if you do art or ‘put pen to paper’, you’re an artist or a writer. The degree of skill has nothing to do with it, although the fact that there are quite a few of us lurking on this side of the screen, appears to indicate a degree of talent. So forget ‘the rules’ and just let the muse come through you. Enjoy yourself dear fellow. We’ll be quietly hanging around eager to see the results. Hugs and best wishes. 🤗🤗😘